My grandpa Herman writes in his memoirs: “Things that I can first remember of is the making of cider. The cider mill was located in a combination building with a work shop. A merry-go-round type one-horse-power rig was on the outside and the power was transferred to the grinding mechanism while the pressing was done with a hand pressure screw…Otto and I were generally the ‘governor’ or speed regulator keeping the horse at a fairly even speed.”

An apple press from the 1800's.

An apple press from the 1800's.“There was nothing wasted in those days, all of the apples that were not sold were made into cider and the pressings that were left were fed to the hogs. The cider was used both for drinking and making vinegar of which about one hundred gallons were sold to stores each year. Grapes were also pressed and made into wine. I can remember one time the pressings were left standing too long and had fermented before being fed to the hogs—they got drunk and really had a good time.”

“By the time winter came, apples, potatoes, and other fruits and vegetables were in the cellar or buried in pits in the ground, hay was in the barn or stacked outside, some was fed to the stock and some sold at five or six dollars a ton. There was timber on the homestead and wood was cut in the woodshed, sugar and flour had been accumulated in exchange for eggs in the stores, a beef and a hog or two were butchered, bacon was smoked in the smoke house, some of the beef was always sold at five or six cents a pound, some was canned or preserved one way or another to keep for a time as there was no refrigeration at the time. A five gallon can of syrup for the pancakes and a five gallon can of coal oil for the lamps were also on hand. Water from the well, no electric or telephone bills.”

“With all of this on hand it appears that there was not much to do thru (sic) the winter but it did not come out that way, wood had to be made for the next year, all by hand with a crosscut saw, split with wedges and sledge and ax. Also general repairs and improvements had to be made. Also during the winter stock had to be fed, the cows milked, by hand, the milk put in pans and placed in cellar until the cream had risen to the top, it was then skimmed off and put into a churn. After the butter was churned mother would take the butter and mold it into two pound rolls covered by a thin paper butter wrapper. This was taken to the stores in exchange for groceries. That which we used was not molded or wrapped.”

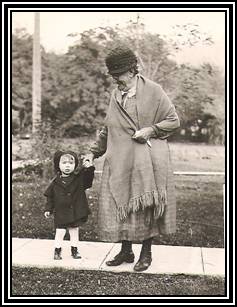

Aloisia and Mathias around the turn of the century. Note the grapes hanging from the eaves of the homestead porch.

Herman and Otto worked very hard year-round on their chores. Like their mother, they drove the cows to and from the pasture with the help of their stock dog, Carlo. Nearly seventy years after Carlo passed away, my grandfather Herman spoke lovingly of this huge, friendly dog who did so much of the work around the farm. According to my mother, “Carlo was every bit as much a part of that family as anyone else. He was a big St. Bernard. So big that my father could ride him to get the cows, just like a horse. Carlo was a big, friendly dog, but he loved to bark. One day, he stood on the train track below the homestead and barked at a train. It ran him over. It was a terrible loss for the boys.”

I remember as a little kid listening to my grandpa tell about Carlo. He said he’d grip Carlo by the scruff on his neck, where he had loose skin and fur, and ride him fast across the fields.

This contemporary photo shows how a St. Bernard could easily carry a young child on its back.

They also helped their mother by turning the clothes through the clothes wringer after Aloisia washed each piece on the washboard. The water had to be pulled from a twenty-five foot deep well. In part because of the tremendous amount of work, the two bright and inventive boys began trying to think up ways to save time and make their mother’s hard life easier. In 1912, when Otto was 11 and Herman only ten, they laid and buried a half a mile of iron pipe from a nearby spring to their house. For the first time, they had running water in the house. They installed a water tank, a water-driven washing machine, and even indoor plumbing.

Herman writes, “This was a great labor saver for mother. She thot (sic) she had everything that would ever be needed.”

Soon after, Herman and Otto built a line to the Juliaetta light system for lights and ironing. Through their enterprising work, the boys became interesting in electricity, telephones, and any type of motor, a hobby which later became their profession.

In 1908, Herman graduated from eighth grade. It was the last schooling he would ever get. Herman notes that most students quit after eighth grade “as there was other work for them to do, either on farms or elsewhere.

Photos of Otto and Herman from this time show the gangly teenagers wearing clothing that is several sizes too small for them. Like most farm families, the Schupfers didn’t have extra money for clothing.

Otto and Herman about 1905.

My mother writes, “According to my father, the marriage was not a happy one, in part because of Mathias’ alcoholism and surely in part because these were two older-than-average people struggling in a new country and in a new language.”

“Grandmother had chickens and a garden. The language spoken in the home was the Styrian dialect spoken in their native land and the children only learned English when they went to school. Otto, Herman and Ida spoke this dialect with one another as adults and always when visiting Grandmother or talking of private matters on the phone. When he was with me in Austria in 1952 the Austrians were amazed at Daddy’s language ability; he used words that had gone out of the vocabulary (schnottern=to talk) and they couldn’t believe he had never been in Austria before.”

On a trip to Austria in 1970, Herman meets with his first cousin Karl Schupfer in Gröbming, Austria, his mother’s beloved mountains in the background. Herman and Karl could speak easily together, as Herman remained fluent in Styrian German dialect until the day of his death.

No comments:

Post a Comment