The Schupfer homestead above Juliaetta, Idaho, circa 1907. Mathias built the house himself. It's still there.

The Schupfer homestead above Juliaetta, Idaho, circa 1907. Mathias built the house himself. It's still there.“The settling down on the homestead was the beginning of quite a chore,” writes Herman. “At this time it had on it a fruit bearing orchard, some of the ground under cultivation, a house and other buildings on it and with money they got from the sale of the property on Potlatch Ridge they bought some cattle, pigs, chickens and whatever was necessary to make a living on the homestead.”

Aloisia feeds the chickens in the farmyard of the Schupfer homestead, around 1907. She traded farm goods to the Nez Perce Indians for fish and other items not available on the farm.

Aloisia feeds the chickens in the farmyard of the Schupfer homestead, around 1907. She traded farm goods to the Nez Perce Indians for fish and other items not available on the farm.“Three children were born. Otto in 1891, Herman in 1892 and Ida in 1896. Times got hard during that time—the 1893 depression, hardly any demand for farm products, some wheat burned for fuel as there was no market for it. A little income was derived from the local sale of eggs (for trade in stores) and a few other farm products. Money was scarce. Some money was derived from the sale of fruit (mostly apples) to the Indians. The Indian (Nez Perce) women would usually come on Sunday afternoon and buy fruit and would stay and visit with our mother. They spoke a different language but mother said they always got along fine and had a good time. Mother enjoyed having them come.”

I can’t help but wonder what the Austrian girl thought when she first encountered the Nez Perce Indians at her farm. It speaks highly of her tolerant and kind nature that she enjoyed them and felt no sense of fear or superiority.

Herman continues, “As the reservation was only a few miles away mother got acquainted with quite a few and had dealings with them and found that they were very honest people, and some time they would get in debt for some time but they always paid as soon as they had some money.”

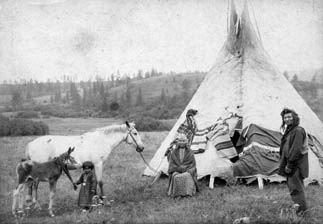

Nez Perce camp at Spalding, about fifteen miles from Juliaetta, 1898.

Nez Perce camp at Spalding, about fifteen miles from Juliaetta, 1898.“Mother said that one time an Indian family had owed them for a long time but the Indian man would come to the house and tell them that he did not have any money yet but would pay as soon as he could. He stopped in a number of times to tell them and on one call he motioned for mother to follow him. She was kind of scared but went with him and he had a large salmon hanging on the wall of a building which he explained was for waiting so long but that he still did not have any money. She had a hard time telling him that was enough for what he owed and when he understood he was a very happy Indian and thanked her very much. Our folks always spoke very highly of the Indians.”

A Nez Perce woman from the reservation near the homestead. She is wearing her finery and has a beautiful beaded purse.

A Nez Perce woman from the reservation near the homestead. She is wearing her finery and has a beautiful beaded purse.This tolerance for other people was passed from Mathias and Aloisia to their three children. Though my grandpa would often use racist expressions, they were more sayings that were in common usage at the time and I never saw him meet anyone, of any color or religion, that he did not hit it off with right away. Everyone was his friend. This gregariousness and tolerance for others was passed on to his own children. My mother Beverly is the same way. She loves interacting with people of other nations and beliefs, and she and my father have passed that on to their children. We, in turn, have taught our kids that God created all men equal and that to think less of anyone is simply wrong. My own saying is ‘Everyone is my equal, and no one is my better’.

No comments:

Post a Comment