To read this blog, you must start at the end and read forwards, as it was posted in that order. Start with intro, then chapter one, etc. This is easy to do by clicking the chapter headings.

The life of Aloisia Knaus Schupfer, my Great-Grandmother

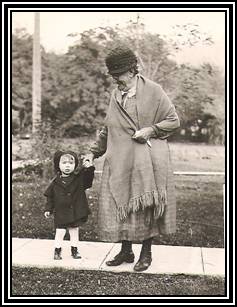

My mother Beverly, with her grandmother Aloisia, about 1932, Kendrick, Idaho.

My mother Beverly, with her grandmother Aloisia, about 1932, Kendrick, Idaho.

“She kept chickens in a coop in the back yard and I helped her feed them by squishing the chicken mash and water together with my hands until it was mixed. I don’t remember then being afraid of birds. I think she also had a cat that at one time had kittens.”

“In the back yard was her ‘refrigerator’, a hole dug into the earth in a shady spot, lined with boards and topped by a board lid. In this she kept butter, eggs and milk to keep cool. In the kitchen cupboard was always a jar of honey, usually sugared, and I was allowed to dig a spoon into it for a treat. She also had raspberry bushes at the edge of her yard and I still associate that fruit with visits to her.”

My mother Beverly with her grandmother Aloisia, about 1931. I believe this photo was taken in her front yard.

My mother Beverly with her grandmother Aloisia, about 1931. I believe this photo was taken in her front yard.“Grandmother knit her own stockings and in my memory they are always red and white striped, like candy canes, but I know better that they were really black, gray or navy blue. While she sat clacking away with her needles she let me have a ball of yarn and knitting needles and allowed me to make a big messy knot with them, while pretending to knit. She must have gotten tired of unraveling the knot, because when I was about five she decided to teach me to knit. I caught on quickly and soon was working on a big pink cap knitted on circular needles. My mother helped me with it, too, and it was finished off with a big pompom on the top and was worn by members of the family until I was in high school.”

“Grandmother always spoke English with a heavy accent and her talk was interspersed with words in the Austrian dialect. She always told me when I left her ‘to be a goot geerl’. Of course, she had not many close neighbors when she lived on the farm and hadn’t the opportunity to speak much English. She had friends who stopped to visit her in her house in town, and they were mainly German speaking. She took a German newspaper published in the U.S.”

Aloisia also read her Bible regularly. I now own her Bible, with her name written in flowing, neat script in the front. The Bible was published in 1877 in New York and is in old German script. It is one of the things I would never part with under any circumstances.

Aloisia Schupfer's German Bible, with her occasional notations and signature in the front, was given to me by my Uncle Otto in the early seventies. It is a prized possession, and links me to her.

Aloisia Schupfer's German Bible, with her occasional notations and signature in the front, was given to me by my Uncle Otto in the early seventies. It is a prized possession, and links me to her.

Train station on the way to Portland, Oregon, circa 1905.

Train station on the way to Portland, Oregon, circa 1905.

Kendrick, Idaho, circa 1910.

Kendrick, Idaho, circa 1910. Bremerton Navy Ship Yard, Bremerton, Washington, where Herman Schupfer worked building ships during World War One.

Bremerton Navy Ship Yard, Bremerton, Washington, where Herman Schupfer worked building ships during World War One.

This photo, sent to me back in the mid-seventies by Uncle Otto Schupfer (Aloisia's oldest son and my great-uncle) shows Otto on the porch and his wife Josephine in the yard.

This photo, sent to me back in the mid-seventies by Uncle Otto Schupfer (Aloisia's oldest son and my great-uncle) shows Otto on the porch and his wife Josephine in the yard. An apple press from the 1800's.

An apple press from the 1800's.

The Schupfer homestead above Juliaetta, Idaho, circa 1907. Mathias built the house himself. It's still there.

The Schupfer homestead above Juliaetta, Idaho, circa 1907. Mathias built the house himself. It's still there. Aloisia feeds the chickens in the farmyard of the Schupfer homestead, around 1907. She traded farm goods to the Nez Perce Indians for fish and other items not available on the farm.

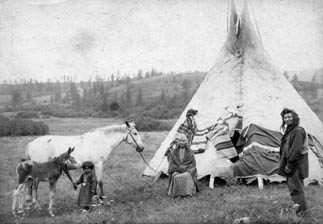

Aloisia feeds the chickens in the farmyard of the Schupfer homestead, around 1907. She traded farm goods to the Nez Perce Indians for fish and other items not available on the farm. Nez Perce camp at Spalding, about fifteen miles from Juliaetta, 1898.

Nez Perce camp at Spalding, about fifteen miles from Juliaetta, 1898. A Nez Perce woman from the reservation near the homestead. She is wearing her finery and has a beautiful beaded purse.

A Nez Perce woman from the reservation near the homestead. She is wearing her finery and has a beautiful beaded purse.